Michael W. Kling and Thomas Gaines | Secretariat International, Inc. | November 28, 2018

Types of damages

The types of additional costs and resulting damages that are experienced by a contractor or owner because of specific events, actions or inactions are likely to vary, but typically include one or more of the following: scope changes, acceleration-related costs, delay-related costs, disruption-related costs and termination-related costs. Rarely will one type of category of damage exist without at least one or more of the others. As such, in most cases, the contractor or owner who has suffered damages will typically experience and claim several different types of damages in an arbitration, unless a total cost claim is being presented. Total cost claims can capture several types of damages in one comprehensive calculation.

Scope changes

Scope changes – modifications to the physical work such as a quantity increase or design revision – are evaluated and priced on a case-by-case basis. Typically, scope changes are priced discretely, which is preferred, though the dispute may focus on entitlement for the claimed scope, pricing of the claimed scope, or the documentation used to support and substantiate the claimed scope. The scope changes may impact both the owner and contractor in different ways. For example, a scope change that increases costs could impact the owner by increasing the overall budget or schedule, or the change could require a variation to a follow-on contractor, which may require some type of design modification. Likewise, a scope change could impact a contractor by increasing the overall budget or schedule, or it could modify the as-bid work plan necessitating more time to complete the project. These are all valid impacts that nonetheless may affect the overall project costs and schedule in some manner.

Assuming the project is complete at the time of the arbitration, damages related to scope changes are normally supported with actual cost information. If the project is not yet complete at the time of the arbitration, damages may be supported with some type of estimate or, more commonly, with a combination of historical actual costs and prospective estimates.

Delay-related costs

When a project experiences delay, the owner is deprived of its finished asset for a period of time and the contractor must deploy time-related resources for a prolonged period.

For a project owner, this may mean lost revenues or extended project management costs, though claims for these types of damages are typically eschewed in favour of the application of liquidated damages. For a contractor, project prolongation can result in extended management, equipment and field operating costs. Field labour and material cost escalation may occur if the contractor’s performance is extended into a period where these resources are more costly than originally anticipated. Occasionally, unanticipated storage expenses will be incurred if materials arrive to site but the project is too delayed to properly receive them. Unabsorbed home office overhead (HOOH) is also a common, if elusive, cost to a contractor facing project prolongation.

Pricing delay damages discretely, based on actual costs, is preferred because indirect costs are commonly impacted, which can make total cost claims appear ambiguous and potentially inflated. Some of the types of delay damages mentioned above, such as unabsorbed HOOH, are virtually impossible to quantify using a total cost method.

The types of delay damages incurred by a contractor will vary based on the nature of the project and its delay, the stage during which delay has occurred, the resources that the contractor has deployed, and whether any delay mitigation measures were taken.

Acceleration-related costs

Sometimes when facing project delays, an owner may instruct the contractor to accelerate its performance. In other circumstances a contractor may be effectively, or constructively, accelerated because of an owner’s refusal to adjust the date for completion when delays are present. In either instance, additional costs or damages are likely to be incurred.

An accelerated contractor may add resources to the project in the form of additional crews, a second or third shift, or by subcontracting a portion of its scope. Alternatively, the contractor may accelerate by keeping the same labour resources but working them additional hours or days during the week or by overlapping activities that were previously planned to occur in sequence. Most acceleration plans will be comprised of a combination of the above options, depending on the realities and restrictions of the project, and its schedule.

Adding labour resources can result in increased costs because of overtime premiums, the cost of subcontracting rather than self-performance (including administering the subcontract) or premiums associated with labour availability. Procurement activities may need to be accelerated to match the recovery schedule, resulting in additional costs in the form of premiums and fees. Depending on the resource levels that the acceleration programme demands, added equipment and supervision may be necessary as well.

Since acceleration is, by its nature, a deviation from the contractor’s original work plan, it will almost always result in some degree of lost efficiency. Accelerating a project schedule will typically entail enacting some sort of change to the original work plan that has been recognised as having a negative impact on labour productivity, whether overtime fatigue, stacking or overlapping of trades that were originally intended to be provided with exclusive access, dilution of supervision, or a litany of other impacts. Disruption is discussed further below.

Since most, if not all, of the acceleration effort is made by the contractor, an owner is typically only concerned about whether it will be funding the effort or not, as a result of liability. Even if not liable, an owner may incur additional supervisory or oversight costs and should be cognisant of the impact that an acceleration may have on any other contracts it is party to, with respect to the overall project. Importantly, a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis should be performed before embarking on an acceleration programme, as most jurisdictions will award a contractor acceleration damages even if the effort was ultimately unsuccessful in recovering time against the schedule.

Disruption-related costs

When a contractor is unable to perform its work in the manner it intended to, or is instructed to deviate from its plan, disruption is likely to occur. Disruption can arise from an almost infinite number of sources, including but certainly not limited to: excessive changes to the work; changes in work sequence; site access or differing site condition barriers; equipment failures or inefficiencies; impediments caused by predecessor or concurrent contractors; weather; overtime; rework; and labour availability.

In a claim setting, the contractor first has the task of proving that the actual condition differed from its plan and that the impact was in no way caused by the contractor’s own actions or inactions. The damage comes in the form of reduced productivity of a project resource, which results in the application of more resources than planned. Most commonly, the additional resources are labour, though equipment can certainly be made inefficient as well. In some cases, it could even be demonstrated that an indirect resource was less efficient than planned and required supplementation, or was more costly.

As with acceleration, an owner will mainly be concerned with its liability for damages, but could be required to dedicate additional oversight resources of its own and might have impacts on other contracts relevant to the project.

Unfortunately, disruption can both be a cause of delay and a symptom of acceleration. In some circumstances, a project could hypothetically be disrupted; the disruption could result in delay; an acceleration plan could be enacted to recover the delay; the acceleration could result in further disruption; and there would be no guarantee that the acceleration would be successful, but the additional costs incurred could be significant for both the owner and contractor.

Termination-related costs

Termination of a contractor is either done for cause (default) or convenience. In cases where default is proven, an owner may put forth a damages claim that relates to the cause of default, be it delay, deficient work, or some other breach of the contractor’s duties. The owner may also claim for the premium cost associated with completing the work, which can be significant considering that the owner may need to enter into a cost-reimbursable contract to complete what may have originally been a lump sum arrangement.

When terminated for an owner’s convenience, the contractor is typically entitled to recover any unpaid incurred costs, as well as contractual or reasonable profit. Valuation of these costs will vary based on the contract arrangement and payment provisions, and will often be subject to a settlement agreement or contract terms when the incurred costs or the contract terms are in dispute in an arbitration.

Pricing methods and models for calculating construction-related damages

There are various types of pricing methods and models that may be used in calculating damages. In some cases, the pricing method is determined by the type of damages, such as scope changes, which are typically built up discretely with actual cost information or estimates. Alternatively, disruption damages may require the total cost methodology or another method depending on the level of project documentation that is available for the analysis. Below are descriptions of several different types of pricing methods or models for calculating construction-related damages that are very typical in the international arbitration context, including the total cost methodology; modified total cost; discrete pricing; extended delay costs using a time-related daily rate pricing approach; recovery of unabsorbed HOOH cost methodology; and disruption and loss of productivity or efficiency analyses (measured mile and industry studies).

Total cost and modified total cost methodologies

In common law jurisdictions, the total cost methodology is a technique used by contractors as a means of proving damages in cases where there are allegations, delays or disruptions during the course of the work that are so pervasive that they cannot easily be segregated and discretely measured in an accurate way.

In general, the total cost approach is simply the difference between as-bid and as-built costs. To successfully pursue a damages claim using this methodology, the following four conditions must be met:

- the nature of the particular losses makes it impossible or highly impracticable to determine them with a reasonable degree of accuracy;

- the bid or estimate is realistic or reasonable;

- the actual costs are reasonable; and

- the contractor is not responsible for any of the added expenses.

The total cost methodology is considered modified when the contractor makes an effort to correct its costs in relation to one of the conditions set out above. This may be to account for its own mistakes or inefficiencies, adjust for a bid inaccuracy or adjust costs deemed unreasonable. Generally, the contractor must not be responsible for any of the added expenses. Though the methodology can be considered controversial and sometimes not preferred, if sufficient project-related cost data is not available to establish and support a specific claim, a contractor may be left with only this methodology in order to try to develop its claim in an effort to be compensated for an alleged breach of the construction contract.

Discrete pricing approach

As mentioned above with regard to scope changes, the discrete pricing approach is often preferred, and can be the most accurate method for quantifying damages when it uses actual cost information included in the contractor’s books and records. In many cases, because the costs are discretely priced, it is possible to tie the actual costs to the specific event being claimed, which makes it easier for the adjudicators to award damages. In some cases, discrete pricing may still use estimates when actual cost information is not available.

The discrete pricing approach can be used for several different types of damages in addition to scope changes, including specific delay-related costs, labour escalation costs, material escalation costs, termination costs, and acceleration or delay mitigation-related costs, all of which have some relation to the overall delay of the project. Below are descriptions of some of these discrete pricing approaches.

Discrete pricing of specific delay-related costs

During a period of delay, the contractor incurs specific time-related costs that can be valued precisely using actual costs. For example, the costs incurred for the contractor’s project management team that are extended on the project longer than planned can be priced very discretely using either agreed-upon rates in the contract or the actual cost information from the contractor’s records. Additional bond and insurance costs can also be discretely priced. Similarly, a contractor may incur extra costs when equipment is idled on the project as a result of delay. In these cases, the contractor can discretely price the cost of the idled equipment using invoices for rented equipment, depreciation cost data for owned equipment, or equipment rate manuals for owned equipment when detailed equipment records are not available.

Labour escalation costs

During a period of delay, it is possible that the contractor’s work may get shifted into a different period of time with an increased labour rate. As such, the hours incurred during the period of the increased labour can be discretely priced with the new or added labour rate amount supported by payroll-related documentation and the increased rates. While seemingly straightforward, in circumstances where the contractor’s work was originally planned to occur in multiple pay periods, pricing the escalation damage can become a complicated exercise.

Material escalation costs

Similar to labour escalation-related damages, a delay on the project may shift the contractor’s planned work into a different period of time with increased material costs. As such, the additional material costs can be discretely priced with the new or added material costs supported by the actual costs incurred, as evidenced by invoices.

Acceleration or delay mitigation-related costs

Similar to costs that may be incurred by a contractor as a result of delay, there may also be costs incurred by the contractor in order to accelerate the work or mitigate delays on the project. Typically, these types of acceleration or delay mitigation-related costs include additional shift work, additional days, overtime, additional project staff and supervision, additional equipment, and additional craft labour and manpower that are discretely priced using the actual costs incurred for the additional resources to accelerate and mitigate the delay.

The issue that arises with respect to these types of damages is normally related to whether the acceleration was in fact directed by the owner and whether mitigation was required to recover the contractor’s own delays or the owner’s delays. As such, entitlement is typically the battleground for the claimed acceleration damages.

Extended delay costs using daily rate pricing approach

Delay damages are one of the more common types of construction-related damages that are incurred by contractors on projects. They are dependent upon a detailed schedule analysis showing and establishing the causes of the increased project duration, which results in additional days to complete the project. Because of the additional days required to complete the project, the contractor incurs additional costs to remain on the project longer, resulting in delay-related damages.

The additional costs or damages incurred by the contractor are typically the time-related direct costs that consist of the general conditions costs that a contractor normally incurs to manage the overall execution of the project, such as the project management team and field office personnel, job site office trailers, job site utilities, temporary power, security, job site safety, equipment, small tools, office supplies, document control and storage. When compiling the time-related costs resulting from an extended project, one needs to ensure that only proper costs are included and remove costs that are either not job-related or would have been incurred regardless of any delay, such as trailer mobilisation, office site prep, etc. After all the general conditions and time-related costs are compiled on a monthly basis (assuming the data is available or organised in that format), a daily rate can be calculated for each month of the project. Once the delay analysis is completed and shows when delays occurred on the project, the monthly daily costs can be used to calculate the extended delay costs, which helps to link the cause-and-effect relationship to the additional or increased costs incurred during specific periods. When the extended delay costs are calculated in this manner, it helps to mitigate and avoid any problems with the cost data owing to the fact that general conditions costs can vary over time depending on the phase of the project, with costs at the beginning or middle of the project likely to be more than those costs incurred at the end of the project.

Although an owner may certainly incur delay-type damages, they are often considered consequential or indirect, or lost profit-related damages. These types of damages are normally waived by parties to a construction contract so they are not typical in an international arbitration. In place of consequential or indirect damages, the parties usually agree to liquidated damages being charged to the contractor for every day of delay to completion or a specific period of delay to completion (e.g., $5,000 per day of delay, or after the first 30 days of delay the liquidated damages are $10,000 and $10,000 for each month thereafter prorated). As such, liquidated damages are much more common in international construction arbitration. In some cases, there could even be liquidated damages for certain interim milestones that are to be achieved during the execution of the project. In many arbitration matters, the delay-related damages of an owner consist of the tabulation of liquidated damages incurred as a result of the delay pursuant to the contract terms. This tabulation is typically a straightforward mathematical calculation of days of delay multiplied by the amount of liquidated damages. The calculated amount is normally supposed to cover the types of consequential or indirect damages that an owner might incur if a project was late, such as loss of revenue or profit, loss of rent, or loss of financing. In general, although each jurisdiction may differ, liquidated damages need to be reasonable under the circumstances. Otherwise, the liquidated damages could be viewed as punitive and not recoverable by the owner. In simple terms, the liquidated damages must be a fair representation of the actual damages incurred by the owner.

Recovery of unabsorbed HOOH costs methodology

The recovery of unabsorbed HOOH is essentially a delay-related damage that may be based on industry sources, local laws, or court or board decisions, depending on the jurisdiction. This damages claim is intended to make whole a portion of the HOOH costs that were incurred and unabsorbed because the project was unable to contribute to recovery of those costs owing to a loss or diminution in revenue on the project caused by a delay or suspension of the work by the owner. The HOOH costs that are part of this type of claim are associated with higher level management and other resources needed to indirectly support the overall company and its projects. These HOOH costs and resources are typically in the home office and not directly billing to the project.[2] Those directly billing to or resources directly related to the project whether on-site or off-site should be included in the field office or general conditions-related costs. This is a delay-related damages claim that has to do with a portion of a company’s overhead costs in the home office and not related to any loss of profits.

Because, arguably, there is no standard way of calculating HOOH, and contracts typically do not provide a methodology for it, it can be a very controversial subject and a point of contention between contractors and owners. Contractors may present damages based on industry formulas to calculate the alleged loss and owners may prefer to use actual cost data or insist on its omission altogether. Because of the nature of HOOH costs and the fact that they cannot be tracked directly to a project, actual damages or cost data becomes difficult or impossible to calculate or even provide at a detailed level. As a result, industry sources, local laws, and court or board decisions become very important, and provide guidelines to parties as to how to establish entitlement and quantum when pursuing or defending a HOOH claim.

In order to recover HOOH costs, a contractor may be required, depending upon the applicable laws, court decisions or contract requirements, to show:

- compensable delay without any concurrent delay;

- substantial reduction in stream of income revenue from project;

- that the owner required the contractor to remain on standby, ready to restart work quickly;

- that HOOH costs were not recovered via paid changes or variations;

- inability to mitigate HOOH damages by taking on new work; and

- inability to perform other work on the project to mitigate HOOH damages.

The above list is not exhaustive, but provided as an example of the potential entitlement-related issues that may be raised with these types of damages. There is a significant amount of research and commentary in the public domain discussing HOOH recoverability, so the above list provides an overview of the issues that may arise in an international construction arbitration context.

Once entitlement is established, the issue becomes one of how to calculate the value of the unabsorbed HOOH. If the actual costs are available they should be used. However, the actual costs or the actual unabsorbed HOOH are rarely available, and may be difficult to calculate, support and substantiate. As such, if actual unabsorbed HOOH is not available, or the contractor can show an inability to calculate, then use of well-known and widely accepted formulas (depending on specific jurisdiction and governing law) are commonly used, including the Eichleay, Hudson and Emden formulas. The usual caveat to using any one of the formulas is that the calculated damages must be considered reasonable under the circumstances.

The original Eichleay formula from a 1960 matter in the United States is as follows, with the three steps taken in the order shown:

Step 1 (Contract billings/Total company billings of actual contract period) × (Total company HOOH of actual contract period) = Overhead allocable to projectStep 2 Overhead allocable to project/Actual contract days = Overhead allocable to contract/DayStep 3 Overhead allocable to contract/Day × Days of owner delay = HOOH recovery amount

The Eichleay formula allocates HOOH of the contract period and determines a daily rate for the delay period. There have also been several modifications of the Eichleay formula in certain instances by using the original contract period versus the actual period or by adding the billings in the extended period in Step 1 in attempts to make the HOOH rate in the original contract period the same during the delay period and to compensate overhead costs over a longer period of time.

The Hudson formula, which was developed in the United Kingdom and is also used in Canada, is as follows:

Step 1 (Planned bid HOOH and profit percentage) × (Original contract amount/Original contract period) = Overhead allocable to project/DayStep 2 Overhead allocable to project/Day × Days of owner delay = HOOH recovery amount (with overhead and profit)

The Hudson formula calculates a daily HOOH and profit rate based on the bid and uses it for the delay period. As such, the result includes both HOOH and profit, which needs to be accounted for in some manner to arrive at the appropriate HOOH amount for recovery.

The Emden formula which was developed in Canada, but is also used in the United Kingdom, is as follows:

Step 1 (Total company overhead and profit during contract period/Total company revenue during contract period)/100 = Overhead and profit percentageStep 2 Overhead and profit percentage × (Gross contract amount/Planned contract period) = Overhead allocable to contract/DayStep 3 Overhead allocable to contract/Day × Days of owner delay = HOOH recovery amount (with overhead and profit)

Similar to the Hudson formula, the Emden formula includes both HOOH and profit, which needs to be accounted for in some manner to arrive at the appropriate HOOH amount for recovery.

There are several other formulas that have been used in the past, depending on the jurisdiction. The Carteret[7]formula and the Allegheny formula date back to the 1950s and have been used in matters in the United States. Both formulas come from the manufacturing industry, but have been used in construction disputes only sparingly. The Manshul formula is one developed by the New York state courts in lieu of using the Eichleay formula. The Ernstrom formula takes a different view of HOOH relationships and evaluates them in relation to overall organisational labour costs. Many other formulas or derivatives exist that may be applicable to select circumstances.

Each of the formulas are used to calculate some type of HOOH recovery for the specific delay period on the project with differences and modifications in each of the formulas. As a result, each formula results in different potential HOOH recovery amounts. The determining factor as to which formula to use is likely to depend on the jurisdiction and governing law of the international construction arbitration.

Disruption and loss of productivity/efficiency analyses

As mentioned above with regard to disruption-related damages, there are many types of issues or events that can cause disruption and loss of productivity on a typical job site. These issues or events could include some combination of the following: acceleration of the work; excessive amounts of change orders in the work; crowding the work site with the stacking of trades; resequencing work or execution of the work in a piecemeal fashion; significant overtime; multiple shifts; reassignment of manpower; crew size issues; weather issues; labour issues; error and omissions; complex construction resulting in learning curve issues; and supervision-related issues and impacts. In addition, each work site has its own characteristics that may contribute to any disruptions and impacts that may affect the execution of the work. All the issues or events that can cause disruption result in impacts to productivity on the project and can cause the contractor to incur losses that are often very significant. As such, proving entitlement to recovery of the disruption and loss of productivity-related issues on the project becomes paramount in order to recover some or all of the losses incurred.

In simple terms and without getting into any specific legal issues, to establish entitlement, a contractor must typically show that the disruptive events, actions or inactions that caused the impacts resulting in productivity issues and additional costs were unforeseeable (not planned), outside the control of the contractor and were the responsibility of the owner. These entitlement issues are typically won or lost with the delay or impact analysis of the project. Once entitlement is established, there are several common methods that are used to calculate disruption costs.

The preferred method is often some type of production analysis, such as a measured mile. This method is particularly useful when the contractor has access to robust resource and production data from the project. When this data is lacking or not available, claimants may rely on published industry studies and papers, which are often specific to certain works, such as electrical or mechanical. The industry studies are even sometimes used as a comparison to other analyses that have been completed to show the reasonableness of the calculated disruption damages. In addition, it should also be noted that the total cost methodology, discussed above, may also be used when sufficient data is not available to precisely calculate the disruption-related losses. For example, use of the total cost methodology may occur when a contractor seeks to recover all or most of its overrun in man-hours because of the disruptive impacts on the project, but does not have the detailed data to conduct a measured mile or even be able to use the industry studies.

Production analysis: measured mile approach

As mentioned, a preferred method for valuing disruption is some sort of production analysis that addresses periodic productivity and highlights the changes over time, ideally in correlation with impacting events. The most popular, and palatable, type of production analysis is the measured mile. A measured mile analysis identifies a period free (or largely devoid) of disrupting impacts and establishes the productivity achieved in that period as the baseline that could have reasonably been expected to continue, but for the disruptive events. The measurement of productivity will reflect the amount of resources required to achieve a certain amount of output or production. This measurement will vary based on the nature of the project, though the most common productivity rate is expressed as units installed per labour hour.

Once a baseline productivity rate has been established, it can be extrapolated into the period in which disruptive impacts were experienced. The result will be a hypothetical resource quantity that can be compared to the actual resource quantity in order to compute the impact. The claimant is effectively asserting that it should have been able to complete its work by deploying x resources, whereas the impacts caused it to deploy y. The value of y minus x becomes the value of its disruption claim.

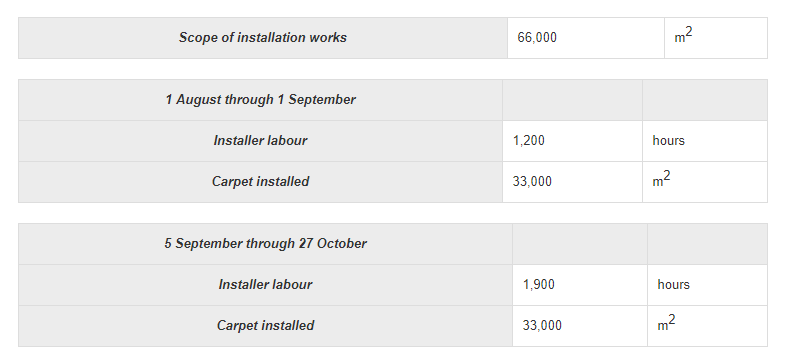

Consider the following example of a contractor performing carpet installation in a school. Project delays have created a situation in which the installer performed half of its work unimpeded in a generally vacant school. The remaining half of its work was performed when school was in session because of a project delay, creating significant access issues that were not originally anticipated.

The contractor identifies the first period as its measured mile, an unimpacted baseline that represents the conditions under which it anticipated performing its entire scope. The contractor then performs the rest of its analysis.

Had the contractor been able to maintain its baseline productivity (27.5 square metres per labour hour), it would have completed the remaining 33,000 square metres of its scope by applying 1,200 labour hours. Because of disruptions, the remaining 33,000 square metres actually required 1,900 labour hours to complete, resulting in 700 hours being lost as a result of disruption. The contractor must then apply its labour costs or rates in order to quantify its claim.

One of the most appealing aspects of a production analysis is the fact that it lends itself to being expressed graphically, which can be beneficial to constructing a viable case. A simple line graph can be compelling, as the production rates can be easily seen over time.

Many similar production analyses exist and can be used as effectively as the measured mile. The main variation is the definition and measurement of output. Some analyses can consider units, such as the example above. Others may measure earned progress, expressed as a percentage. While the details may vary, the underlying concept of baseline extrapolation remains.

While seemingly straightforward, many potential pitfalls exist when preparing a production analysis such as the measured mile. Establishing causation, accounting for other productivity impacts, and ensuring that the work in the unimpacted period is sufficiently similar to that in the impacted period are issues that should be considered. Certain data analysis concerns must also be addressed, such as avoiding ramp up and down inefficiencies in the measured mile and ensuring that the baseline productivity rate encompasses an adequate amount of the total scope of work. In many cases, the resource and output data collected by the contractor is simply inadequate or the work varies to such a degree that a production analysis is not feasible. In these cases, another method of quantifying disruption must be found.

Production analysis: industry studies

With respect to the use of industry studies in evaluating productivity, the more common studies that may be used in a construction arbitration context are the following:

- The MCAA Study – Loss of productivity curves of the Mechanical Contractor Association of America, Inc (MCAA), which provide 16 different productivity factors and categorise the percentage of loss as minor, average and severe, ranging from 5 per cent to 40 per cent.

- NECA studies – The National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA) has published multiple studies on productivity loss, one of which focuses exclusively on impacts resulting from prolonged overtime programmes.

- Leonard curves research – Research that provides various levels of productivity loss based on the percentage of the amount of change orders across 57 different electrical and mechanical jobs.

- Ibbs curves research – Research that provides various levels of productivity loss based on percentage of the amount of change orders across 162 different highway, commercial and industrial jobs.

The MCAA industry study suggests that when one considers some or all of the 16 productivity factors in the study, one can develop an estimate of the loss of productivity experienced on any particular project. Below is a list of the factors from the MCAA industry study (with the percentage of minor, average and severe productivity losses shown in parenthesis):

- trade stacking (10%, 20%, 30%);

- morale and attitude (5%, 15%, 30%);

- manpower reassignment (5%, 10%, 15%);

- crew size (10%, 20%, 30%);

- concurrent operations (5%, 15%, 25%);

- dilute supervision (10%, 15%, 25%);

- learning curve (5%, 15%, 30%);

- errors and omissions (1%, 3%, 6%);

- beneficial occupancy (15%, 25%, 40%);

- joint occupancy (5%, 12%, 20%);

- site access (5%, 12%, 30%);

- logistics (10%, 15%, 20%);

- fatigue (8%, 10%, 12%);

- ripple (10%, 15%, 20%);

- overtime (10%, 15%, 20%); and

- weather change (10%, 20%, 30%).

As can be seen from the list above, the 16 factors from the MCAA industry study range from 1 per cent to 15 per cent for minor productivity losses, 3 per cent to 25 per cent for average productivity losses and 6 per cent to 40 per cent for severe productivity losses.

In using the MCAA study to quantify disruption, one selects the factors that apply to the manner in which the project was executed and likely attributed to the loss of productivity on the project. An example may be a project that has suffered a significant increase in man-hours because of productivity impacts, but the records lack the resource and output data necessary to complete a measured mile analysis.

A simple table showing the actual hours by period with the relevant MCAA factors applied can also be compelling, as the additional hours can be calculated and shown by period.

Similar to the MCAA study, which is related to mechanical work, there is a series of productivity studies for electrical work published by the NECA. One of the key studies, which is used in a similar manner to MCAA, focuses on losses of productivity resulting from overtime worked on a project. The data included in both the MCAA and NECA studies are based upon survey information from contractors and not actual job productivity information.

The Leonard curves research, which was based on 57 different electrical and mechanical projects, correlated the amount of change order hours issued on a project to a corresponding loss of productivity. Knowing the percentage of change orders incurred on a project, one can determine an estimated loss of productivity using the Leonard curves.

The Ibbs curves research, which was developed from a study of 162 different projects related to highway, commercial and industrial projects, also correlated the amount of change order hours issued on a project with an expectant loss of productivity. Again, knowing the percentage of change orders incurred on a project, one can determine an estimated loss of productivity using the Ibbs curves.

In general, if no other data is available to quantify the disruption impacts but industry studies, one must proceed with care when using any of the above studies because the quantification is merely an estimate and there are many potential pitfalls that exist, as with any type of disruption-related quantification.

Using the MCAA or NECA studies to quantify impacts is very subjective and could result in large, and potentially overstated, loss of productivity claims when multiple factors are potentially at issue because of the manner in which the project was executed. Using the Leonard and Ibbs curves could also result in substantial, and possibly inflated, loss of productivity claims if significant change orders were experienced on the project, and subjectivity may also be an issue in selecting which of the three Leonard Curves to use. In addition, a common problem at times with all of the industry studies is that the project at issue may not be very comparable to the projects that were included or evaluated as part of the studies. As such, it is important to ensure the work on the project at issue is somewhat similar to the work included and evaluated as part of the industry studies.

In general, when using the industry studies, it is best to compare the result of the productivity studies analyses to the actual losses incurred, or a total cost approach, and determine whether the studies produce a result that appears fair and reasonable under the circumstances.

Conclusion

Regardless of the types of damages experienced and incurred, the complaining party, whether the contractor or owner, must be able to prove its damages and then be able to clearly support and substantiate them with the appropriate level of documentation. This typically does not require a document for every dollar claimed as damages, but it does require some level of supporting documentation, which may depend on the agreement between the parties as to document requests and production.

Overall, the exactness of the claimed damages is not a prerequisite for recovery, but it is critical to show, establish and calculate damages with a reasonable degree of certainty so that the adjudicator or arbitration panel is in a position to understand the damages, and be able to associate the additional costs and resulting damages with the underlying events, actions or inactions that were the primary cause of the claimed damages. When construction-related damages are supported and compiled in the appropriate manner, the complaining party is, more likely than not, in the best position to allow the adjudicator or arbitration panel to rationalise why all or some level of compensation is appropriate for the claimed damages.