Lynette Khoo, Kia Jeng Koh and Pat Lynn Leong | Dentons

Introduction

We are at the cusp of a COVID-19 pandemic. In our earlier articles on COVID-19, we focused on force majeure and the legal doctrine of frustration, specifically in the context of how construction delays may impact a contractor’s obligations to the developer under the construction contract.

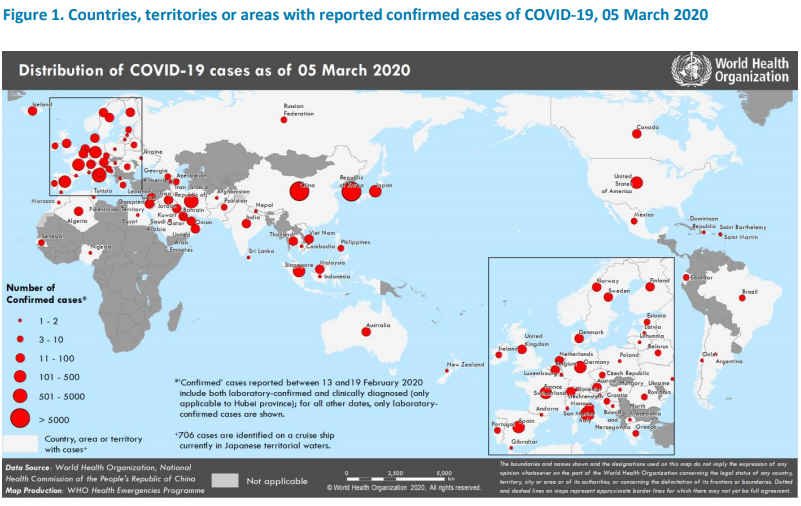

Since then, COVID-19 has travelled far and wide. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s Situation Report No. 45 based on data as of 5 March 2020 (SR 45), COVID-19 has hit over 80 countries and crossed most continents. We reproduce Figure 1 from SR 45 found on WHO’s website:

Every day, we read and hear reports of short supply of labour, factories still closed, gradually opening and even if open, not operating at full capacity. The outbreak has reportedly caused massive disruptions to global manufacturing, transportation and cross-border supply chains.

In Singapore, this is an acute problem for contractors, because most of the building and construction industry’s materials, plant and equipment, and labour come from everywhere except Singapore – this includes Portland cement, marble, tiles, chipboard, appliances, screws and even epoxy resin! With the adoption of pre-fabricated pre-finished volumetric construction (PPVC) in many building development projects in Singapore, one can surely imagine the repercussions on the construction process even when there is only one missing item.

It is no surprise, then, that some contractors are already asserting and/or making force majeure claims. With the number of such claims likely to rise in the coming weeks, we turn now to focus on the position of the developer – how do construction delays potentially impact the developer, and in particular, the deadlines which may be imposed on the developer by various other third parties?

Deadlines Imposed on Developers

In a building development project, the developer may be subject to various deadlines which relate to construction milestones and/or are dependent on timely completion of the project under the construction contract between the developer and the main contractor. Such deadlines are imposed by various third parties, such as government agencies, individual end purchasers and lenders.

We summarise below some examples of such deadlines, as well as some practical tips for the developer:

| Nature of Deadline | Consequences if Deadline is Not Met |

|---|---|

| Qualifying Certificate (QC) regimeGovernment Agency – Controller of Residential Property, Singapore Land Authority (Controller).Deadline – The QC typically requires the developer to complete the construction of the whole housing development and obtain the Temporary Occupation Permit (TOP) for the whole housing development within 5 years from the date of the QC (QC Deadline). The QC is usually backed by a banker’s guarantee or insurance guarantee for 10% of the land price (QC Security). | The Controller may forfeit the QC Security.Practical Tips -If the QC Deadline is approaching, it would be prudent for the developer to review, and promptly apply to the Controller for an extension of the QC Deadline.The extension charge payable is 8% of the land purchase price for the 1st year of extension; this goes up to 16% for the 2nd year and 24% per annum for the 3rd and subsequent years.It is hopeful that the Controller will grant a waiver of or reduction in the extension charge, in view of events impacting the whole world and the local building and construction industry arising from the COVID-19 outbreak.Alternatively, if the developer is a publicly listed housing developer with a substantial connection to Singapore, the developer may also consider applying for exemption from the QC regime (pursuant to the new ground of exemption introduced on 6 February 2020). |

| Government Land Sales (GLS) programmeGovernment Agency – The State and its appointed government land sales agent (for instance, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)).Deadline – The Conditions of Tender and the Building Agreement (GLS Sale Conditions) for all GLS sites require the developer to construct and obtain TOP for the whole of the development within a specified project completion period (typically 60 months from the date of tender acceptance or longer, depending on the specific project) (PCP Deadline). | This is usually an event of default under the GLS Sale Conditions.The GLS Sale Conditions usually do not contain any force majeure provisions which operate to suspend or excuse the developer’s performance of its contractual obligations, including its obligation to meet the PCP Deadline.Practical Tips -If the PCP Deadline is approaching, it would be prudent for the developer to review, and promptly apply to the relevant government land sales agent for an extension of the PCP Deadline.The extension premium payable is 8% of the tendered land price for the 1st year of extension; this goes up to 16% for the 2nd year and 24% per annum for the 3rd and subsequent years.Based on URA’s Circular on Extension Premium Scheme, the prevailing policy is that extensions of the PCP Deadline, without any charge or payment, will be granted for delays in work progress due to reasons beyond the developer’s control (for instance, unexpected technical problems in developing the project). It is certainly the case that construction delays arising from the COVID-19 outbreak are “reasons beyond the developer’s control” and it seems likely that these delays should be regarded as such for the purposes of URA’s Extension Premium Scheme. |

| Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD) regime – remission for housing developersGovernment Agency – Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS).Deadline – As part of its undertaking to IRAS in exchange for the upfront remission of ABSD, the developer is required to (i) commence housing development on the site within 2 years from the acquisition date and (ii) complete the housing development and sell all housing accommodation therein within 5 years from the acquisition date. | The developer is required to pay to IRAS an amount equal to the ABSD remitted, together with interest thereon at the rate of 5% per annum computed from 14 days after the acquisition date. To note the ABSD payable is not on a pro-rata basis.The applicable ABSD rates are available on IRAS’ website. |

| Housing Developers Rules (HDR) regime – for licensed housing developersPurchaser – Individual end purchaser of the unit.Deadline – Under the prescribed forms of the Option to Purchase and the Sale and Purchase Agreement (HDR Sale Conditions), the developer must specify the latest date for delivery of vacant possession of the unit (Vacant Possession Deadline). | The developer is required to pay to the purchaser, liquidated damages (LDs) calculated on a daily basis at the rate of 10% per annum on the total sum of all instalments paid by the purchaser towards the purchase price.The HDR Sale Conditions do not contain any force majeure provisions which operate to suspend or excuse the developer’s performance of its contractual obligations, including its obligation to meet the Vacant Possession Deadline. Force majeure provisions in the facility agreement, if any, typically operate in favour of the lender. Practical Tips -For unsold units – It would be prudent for the developer to amend the Vacant Possession Deadline to be specified in each Option to Purchase/Sale and Purchase Agreement to a later deadline. This is to minimise the risk of incurring LDs in respect of new sales.For sold units – LDs will be payable if the Vacant Possession Deadline is not met, unless the developer is able to negotiate other options with the purchaser. |

Concluding Thoughts

If the main contractor succeeds in pushing back the completion date under the construction contract legitimately, on account of its Extension of Time (EOT) claims based on force majeure, this means that the main contractor is likely to be relieved from its obligations to pay LDs for the excused period.

What happens to the developer, and its separate deadlines vis-à-vis the various third parties, then?

- Will the developer be correspondingly relieved, in relation to the deadlines imposed under the QC regime, the GLS programme and the ABSD regime? Given the ongoing global impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, it is hoped that government agencies/the State lessor will review developers’ requests for EOT favourably (as they have done in previous crises). It is encouraging to note that the government has indicated that it is monitoring both the construction industry and the property market closely, that it will adjust its policies as necessary to ensure a stable and sustainable property market, and that it is prepared to adopt a case-by-case approach for projects which need help (see The Business Times article published on 5 March 2020 for more details).

- Will the developer be correspondingly relieved, in relation to the deadlines imposed under its loan financing arrangements? The lender may not immediately declare an event of default and call for repayment of the loan. Nonetheless, in the case of a housing development project, a slower pace of construction and/or a significant delay in the anticipated date for obtaining TOP for the development, will result in slower collections by the developer of progress payments from individual end purchasers (and possibly also a slower pace of new sales of units in the development). This ultimately translates into higher interest costs for the developer.

- Will the developer be correspondingly relieved, in relation to the deadline imposed under the HDR regime (i.e. from paying LDs to the individual end purchaser)? It seems not, given the absence of any force majeure provisions in the HDR Sale Conditions. While it is unlikely that the purchaser will be able to rely on the legal doctrine of frustration to terminate its purchase of the unit, the considerable quantum of LDs payable by the developer for each sold unit in the development is already fairly penalising to the developer. We hope that, for most developers who have otherwise been able to achieve a good pace on their construction, with adequate buffers built into the Vacant Possession Deadline in the Option to Purchase/Sale and Purchase Agreement, and with continued efforts of government agencies and communities to stem the spread of COVID-19, the consequences of LDs can be avoided and/or minimised.

Hence, there appears to be real asymmetry between the developer and the main contractor, especially under the HDR regime. Perhaps it is time to rethink the prescribed form of contract for the developer and the individual end purchaser (i.e. the HDR Sale Conditions) and/or manage the developer’s risk vis-à-vis the individual end purchaser by amending the construction contract that the developer enters into with its main contractor.